The prevailing narrative in Singapore’s road safety campaigns often relies on the language of symmetry. We are frequently told that “It takes two hands to clap” or that safety is a “Shared responsibility” between motorists, cyclists and pedestrians. While these slogans are well-intentioned attempts to foster mutual respect, they ignore the fundamental laws of physics. By treating a two-ton SUV and a sixty-kilogram pedestrian as equal partners in safety, we obscure the reality of risk and the moral weight of operating a lethal machine.

To move toward a truly sustainable road system, we must move away from the “shared responsibility” fallacy and adopt a framework of responsibility: the duty of self-preservation and the duty of care.

The Fallacy of Symmetrical Responsibility

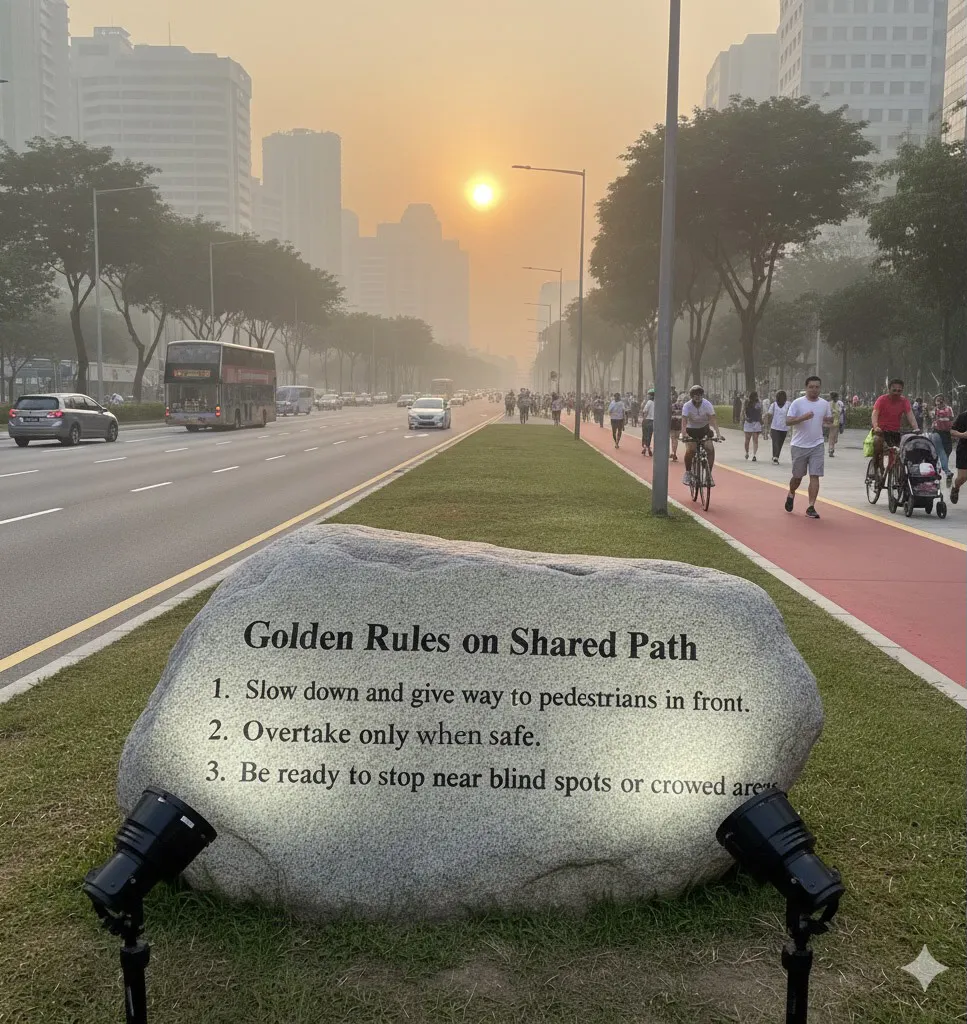

Public safety messaging, such as that from the Singapore Road Safety Council, often implies that because both parties are present in a collision, both are equally responsible for preventing it. This is a logical category error. In any interaction between a motorized vehicle and a vulnerable road user (pedestrians, cyclists, or personal mobility device users), there is a massive disparity in kinetic energy.

A car does not just move a person from point A to point B; it acts as a potential weapon. Therefore, the responsibility for the safety of others cannot be shared equally. It must scale with the lethality of the machine being operated.

Principle 1: The Responsibility for Self-Preservation

Every road user, regardless of their mode of transport, is responsible for their own safety. A pedestrian looks both ways before crossing a street not because they owe it to a driver to stay out of the way, but because they have a natural interest in their own survival.

When a pedestrian is told “not to jaywalk” or to “cross only at designated crossings,” the implication is often that any movement outside of these bureaucratic lines makes them the primary author of their own misfortune. However, a pedestrian “jaywalking” is simply a human being following a “desire line”—the most direct path to their destination. While they should be cautious for their own sake, their failure to use a designated crossing does not absolve the operator of a heavy machine from the responsibility of not hitting them.

Principle 2: The Duty of Care and the Lethality Index

The second, more important aspect of responsibility is the duty of care toward others. This is where the “shared responsibility” narrative fails. In a physical sense, it is impossible for a pedestrian to threaten the life of a car driver. A cyclist cannot kill a van driver through a lapse in concentration. Because the vulnerable group poses zero physical threat to the motorized group, they are physically incapable of sharing the “duty of care” for the motorist’s safety.

The responsibility for the safety of others must rest solely on the individual who chooses to operate the more powerful machine. If you are the one controlling the kinetic energy that can end a life, you carry the burden of ensuring that your machine does not harm those around you.

Challenging the “Two Hands to Clap” Narrative

When we say “it takes two hands to clap” in the context of a motorist and a cyclist, we are suggesting that the cyclist has an equal ability to prevent a tragedy. This shifts the focus away from the driver’s professional and moral obligation to maintain a safe environment.

The concept of “jaywalking” is a prime example of this shift. Historically, the term was popularized by the auto industry to reclaim the streets for cars, moving the “shame” of accidents onto the people walking. By labeling every crossing outside of a narrow, often inconveniently located stripe of paint as “illegal,” we criminalize natural human movement and create a cheap excuse for system designs that prioritize motorists’ speed over human life.

Toward a Hierarchy of Responsibility

A truly safe road system recognizes this hierarchy. In such a system:

- Pedestrians and Cyclists are encouraged to be aware for their own self-preservation.

- Motorists are held to a higher standard of “Duty of Care” because they are the ones introducing risk into the environment.

- System Designers recognize that humans will always make mistakes and design roads that make it physically difficult for a driver to exercise their power in a lethal way.

Safety is not a 50/50 split. It is a weighted obligation. The more power you wield, the more responsibility you carry for the lives of those who do not have that power. Until our road safety campaigns reflect this physical reality, we will continue to blame the vulnerable for the failures of the powerful.